Eggshells on Paper

Each a finely developed visual/symbolic statement, with surfaces made of minute particles of broken eggshells graded according to a colour-tone scale of whites to soft-browns, the works on view emanated a warmth, a presence of profound enriching optimism. William Wright, 2009

On the materiality of eggshells

A perfect form, a perfect food, spirit and flesh; the egg is an integument (a natural covering, as a skin, shell or rind) of life, symbolising fragility, birth and death, even as it is part of everyday life. Creation and destruction are mutually dependent – ‘you can’t make an omelette without breaking an egg’. In shattering and reconstructing the fragments, laying inside and outside side-by-side, these works rupture and recreate meanings, gesturing towards a different relationship between the Self and the Other.

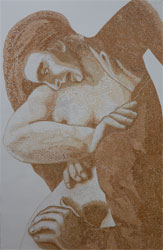

Other to me

2008

eggshells on paper, plaster arch,

300 x 200cm x 100cm, eggshells on floor of variable dimensions

complex and powerful at a profound level

Marion Quartly, Professor Emerita, School of Philosophical, Historical and International Studies, Monash University, 2009

A naked woman wrestles with a clothed man who is formed of her own body. Their violent encounter is suggestive of a sexual assault, but it could also be a struggle with one’s opposite, or with that one most fears in oneself. She may be wrestling with her own demons, rejecting and attempting to eject a part of herself.

I’ve chosen to materialise the image to the scale of my own body to amplify its power and to employ the shattered eggshells for all the qualities discussed below in relation to the Facing the Other suite. The eggshells, especially in this work, approach the microscopic in size, aiming to capture and hold the viewer’s attention as the eye sweeps over and into the work. The beauty of the pearly eggshells and the obvious labour involved in this large work, are means by which to engage the viewer’s attention, encouraging a slowing of time for different layers of the work to be absorbed.

We often project onto the Other that which discomforts or threatens us about ourselves, and then attempt to expel that supposedly sinning Other, who becomes the scapegoat. Historically, expulsion has been the primary Western response (represented by the Victorian plaster arch), to difference.

The strewn eggshells on the floor in front of the work may have loosened in the struggle to expel the Other or suggest the difficulty of confronting these issues. Treading on the eggshells, either deliberately or by chance, involves and implicates the viewer in the work’s meaning.

Facing the Other series

2008

eggshells on paper

French Lithuanian philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas’ radical conception of alterity, his bold response to the reality and the shadow of the Holocaust in tandem with his poetic terminology have been a rich creative source for these works, as have Surrealist Magritte’s Titanic Days, Rubin’s figure-ground vase, the Talmud and The Wizard of Oz. Lévinas’ articulation of the encounter with the Other has inspired a number of paintings and eggshell works on paper which respond to his poetic use of terms such as transcendence, infinity, the exteriority of the Other, Le visage (the face) and le face à face (the face to face).

Facing the Other (1) is based on the Rubin’s vase or figure-ground vase, which belongs to a famous set of cognitive optical illusions developed circa 1915 by the Danish psychologist Edgar Rubin. The image presents the viewer with a mental choice of two interpretations, two profiles or a vase, demonstrating the figure-ground distinction the brain makes during visual perception. It is impossible to see both interpretations simultaneously, one flips between the two. Figure and ground, subject and object, which is the correct, which the dominant reading?

I am interested in Lévinas’ conception of the face, as the condition of the Other’s separateness and the conduit through which alterity presents itself, “the encounter with a face which at once gives and conceals the other.” In the ‘face to face’, the Other is neither with nor against the self, but the nature of the encounter is originary, irreducible and fundamentally ethical. The Other, in Lévinas’ face is prior to identity, even prior to the distinction between object and subject, imbuing my subjectivity and freedom with meaning. “The way in which the Other presents himself, exceeding the idea of the Other in me, we here name face. This mode does not consist in figuring as a theme under my gaze, in spreading itself forth as a set of qualities forming an image. The face of the Other at each moment destroys and overflows the plastic images it leaves me, the idea existing to my own measure and to the measure of its ideatum - the adequate idea.

Le visage (the face) and le face à face (the face to face) may be Lévinas’ most memorable, paradoxical and problematic terms because visage both does and doesn’t refer to real human faces. The face is the most visible, accessible and expressive part of the body - ‘expressive’ suggesting a source of meanings emerging from elsewhere. But to simply see the face would be to make of it an object of perception and knowledge, thus reducing its absolute otherness. Rather it is an epiphany or disclosure, “it is something that is not available to vision, but described as if it were, signalling an encounter which is not an event, and an experience which does not occur in the consciousness of any subject.”[1]

Transcendence, in the sense of rupture and opening up to the Other, occurs in the face to face, making ethics possible because it goes beyond the brute fact or power struggle of the encounter. Facing the Other (2) reflects on Lévinas’ approach to trancendence. It depicts the moment in the film The Wizard of Oz, in which the twister lifts Dorothy’s house, transporting her to Oz. Swept up into the maelstrom, pitched into the sublime, “apprehending subjectivity as founded in the idea of infinity”[2] Dorothy discovers herself when confronted with the Other, the encounter affirms the Self, but does not subsume, nor is it subsumed by it.

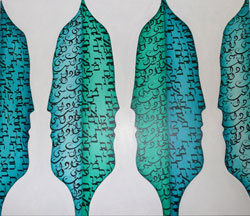

Sarah and Hagar

2009

emu eggshells on paper, 100cm x 68cm

The Biblical narrative of Sarah and Hagar encompasses issues of fertility, slavery, surrogacy, status and inheritance. As the first encounter in the histories of Judaism and Islam, it resounds with tensions which reverberate through the contemporary conflict.

The words Isaac (in Hebrew) and Ishmael (in Arabic) replace the women's eyes in this face to face encounter. Their placement within the attenuated faces suggests Sarah and Hagar are only able to see each other in terms of their sons, underlining the Biblical measure of a woman as her ability to produce (preferably male) offspring. The women are so close they can see the whites of each other's eyes and yet so far apart that they have in a sense, become blind to each other's humanity.

The emu eggshells' dark green tones suggest the jealousy, fear, sacrifice and shifting power of their relationship while also referencing Australia, where conflicts of inheritance and possession form part of our landscape. The shattered and reconstituted eggshells, with inside and outside laid side-by-side, represent both creation and destruction.

Facing the other: there’s no place like home

2008

Acrylic on linen, 100cm x 100cm

Facing the Other: there’s no place like home is the first of a series of paintings that interprets ideas of discourse and the unequivocal welcome of the stranger, incorporating calligraphy from each protagonist’s own language and culture. The figure ground image has been attenuated and the faces read ‘there’s no place like home’ transcribed in both Hebrew and Arabic. Building on the ideas expressed in Facing the other (1) and (2), the phrase references the turbulence of being uprooted, resonating beyond Dorothy’s longing for Kansas, to express the tension and prejudice that exist between Israelis and Palestinians over disputed territory which each call home. Lévinas’ conceptions of the face, discourse, the infinite and the unequivocal welcome to the stranger inform this encounter between two peoples who are Other to one another.

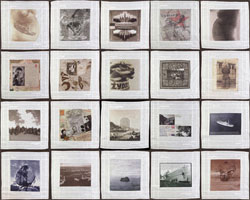

Displaced Persons

2003

20 linen handkerchiefs with archival ink transfers and embroidery,

40cm x 40cm each,

overall size: 200 cm x 160 cm.

The word `refugee’, which should pull at our heartstrings, has instead been reduced in this country to a pejorative revisionist lie of `queue-jumper’, `bludger’ and, at its most extreme, ‘terrorist’. This artwork brings us back to the truth...It is beautiful, political and inspirational.

Brett Sheehy, Sydney, Adelaide and Melbourne Festival Director, Object Launch #01, 2003

Displaced Persons, a collaboration with photomedia artist Anne Zahalka, was created in 2003 for the Isle of Refuge exhibition. Beginning its national tour at the Ivan Dougherty Gallery in Sydney, the exhibition brought together a “group of prominent Australian visual artists who, through their personal histories, ethics and politics, have a special sense of solidarity with refugees in detention in Australia and in Australian camps in the South Pacific.”[3] Artists who came to Australia as refugees, migrated because of political or racial pressure or persecution, and those who are the children of refugees, émigrés and migrants, created works in protest over the treatment of refugees involved in the Tampa incident.[4]

Displaced Persons was selected for the 16th Tamworth Biennial Fibre exhibition curated by Suzie Attiwill and toured NSW and Victoria for two years. Three editions of the five editions have been sold to the National Maritime Gallery of Australia, The Jewish Museum of Australia and to a private collector.

Displaced Persons charts the journeys of our two families from Europe to Australia through the layering of photographs and personal documents from our family archives. The images map the reasons they fled their homeland and the emotional and physical landscapes they encountered in their search for a new life.

Travel and immigration documents, emblematic anti-Semitic and Communist propaganda and nostalgic images of Hungary and Czechoslovakia were transferred onto twenty handkerchiefs, creating the context of both the physical and psychological journeys undertaken. Images projected onto a pregnant belly insinuate a sense of prejudice written on the skin, inscribing notions of racism and suspicion of the Other both internally and externally, of being born into a certain history by which we are defined. For Anne and me, the making and exhibiting of Displaced Persons acknowledged not only our families’ struggle to find a safe place to live and flourish, but for the difficulties faced by all refugees.

| LIST OF WORKS | |

| refuge /refugee | the Surriento, the ship which brought our parents to Australia in 1950, projected onto the body |

| enemy /alien | map of Nazi-occupied Europe |

| home /homeless | Austrian document proving residency |

| possess /dispossessed | map of Soviet occupied countries |

| hate /hope | the Jewish star printed in Germany as a fabric cut-out |

| szasz /saxon | name change to assimilate into Australian society |

| tokaj /bondi | the young Szasz Bandy in the family vineyards in Hungary |

| vermin /jew | Polish antisemitic imagery projected onto the body |

| homeland /homesick | Czech embroidery with photograph of the family's hop farm in Rochov |

| vaclav /paul | portrait of Vaclav Zahalka with statement outlining his participation in fighting with the allies |

| strange /stranger | The Pinnacles, Western Australia, with text from The Castle by Franz Kafka |

| identity /processed | documents including UN displaced persons refugee identity cards |

| countryside /genocide | in 1944, Germany knew it had lost the war but continued to round up the Jews of northeastern Hungary and transport them to Auschwitz |

| occupied /outcast | two views: postcard of postwar Prague doubled with postcard of anti Soviet occupation |

| antipodes /exile | the Surriento with Zahalka anecdote |

| place /displace | Balancing Rock, Northern Territory, with text from The Castle by Franz Kafka (in Hebrew) |

| arrive /survive | aerial view of Sydney Harbour Bridge by Frank Hurley |

| berth /land | Landing Permit, Department of Immigration |

| foreign /foreigner | the Surriento with Saxon anecdote |

| native /citizen | boab tree in Derby, Western Australia, used as a lock-up in the 1800s |

The Bride veiled by time

2002

installation views: seven x 1.8m x 3.8m silk organza veils in colours ranging from black through blues to white.

The Bride veiled by time was commissioned by the Jewish Museum of Australia, Melbourne, for the exhibition On the Seventh Day.

A central doorway must be drawn aside to pass through the veils. Each progressive doorway increases in size as the colour of the veils becomes progressively lighter. The doorway shapes are based on the iconography of medieval Ketubbot (Jewish wedding contracts). Each veil has a small image at, or slightly above, eye level with text naming the days of the week from Yom Rishon (Sunday) to Shabbat (the Sabbath). The images range across the world of work with each image depicting more complex, technological or stressful work ie from manual labour through to stockmarket activity.

The seven veils reference the conception of Shabbat as the bride and as the Shekhinah, the feminine aspect of God, who rests with and within us. The Bride veiled by time draws on the idea of Shabbat as the wedding of the Holy One with the Shekhinah.

In moving through the piece, the act of drawing aside each veil suggests movement through the days of the week, the ‘days of Creation’, in the path to the day which confers meaning upon both. The Bride veiled by time is Abraham Joshua Heschel’s idea of Jewish ritual as ‘the art of significant forms in time, as architecture of time’. Architecture, usually associated with space rather than time, is present in the site-specific quality of The Bride veiled by time, its encompassing physical presence and in the doorway structures. The work is a metaphor for moving through time, as well as a sensuous visual and physical experience. Drawing aside the veils suggests an act mixed with reverence and tenderness as well as referencing the sensuousness of a time in which it is considered holy to consummate the bond with one’s partner.

Chainmail boots and suspender belt

2001

fine French chainmail, magnets, stainless steel, aluminium, leather

This work was created in Paris while on an Australia Council residency at the Cite in the Marais precinct. I wanted to embody the effect a pair of beautiful shoes inspires in our psyches - an almost fetishistic, irrational desire. I wanted the shoes to be seductive, dangerous and to a degree impossible, which is why they are made of a material as intriguing and resistant as chainmail.

I like the fact that the current use of this material is butchers' safety equipment - gloves and aprons worn while preparing meat for consumption, and the fact that chainmail was originally worn into battle - perhaps these boots belong in every contemporary woman's armoury.

The work was exhibited in the travelling Hermanns Art Award exhibition which toured NSW and Victoria.

The tears I cried for you

1998

5 x 1.8m x 30cm, 35 glass lachrymatories, tears, stainless steel, wax, cork, labels

Turning on the tension between emotion and reason, the body and the mind, the sensual and the conceptual, the tears I cried for you reflects on the consequences of attempting to classify and control humanity. “Who will write the history of tears?” French philosopher and semiotician Roland Barthes’ asks.[5] The tears I cried for you is a contribution to an alternative history, the yet uncatalogued history of emotion.

Comprising 35 glass vials or lachrymatories The tears I cried for you toured Australia as part of the Water Medicine exhibition curated by Kevin Murray in 1998. Lachrymatories were discovered in Greek, Roman and Hebrew tombs and held the tears of relatives and friends of the deceased, as well as professional mourners. The vials, which played a significant role in funeral rites, were sealed and buried with the dead as both tribute and a form of catharsis.

I distributed 100 hand-blown vials which were based on a tear shaped Roman

lachrymatory in the collection of the Nicholson Museum, Sydney University, to participants of different cultural, political, sexual and social backgrounds. I asked each contributor to choose one facet of their identity, and note the date and reason for shedding tears. This brief description accompanied each of the thirty-five vials returned to me, which contained tears of varying amounts and degrees of cloudiness.

I was interested in the act of crying, the paradoxical project of making conscious and public a generally private involuntary action. To this effect, the lachrymatories were hung on stainless steel stands, each with a cardboard label attached, mimicking museological tradition. The vials’ diverse emotional, ephemeral content together with the work’s title provided stark contrast to the detached objectivity claimed by their display.

The concept and presentation of my installation The tears I cried for you draws on Linnaeus’ system of classification which influenced a racial hierarchy where Europeans were ranked at the peak. Members of many European countries used the classification scheme to validate their conquering or subjugation of members of the ‘lower’ races, categorised as Other. In particular, Linnaeus’ concept of race was used to enforce the inhumane institution of slavery, particularly in the new world European colonies. My work is informed by this history, and the resulting dehumanisation and exploitation.

| The tears collected in the lachrymatories include: |

| tears of sorrow at the suicide of a friend’s teenage daughter |

| tears shed by a widower |

| tears shed by an Aboriginal woman while watching Oprah |

| tears shed to win sympathy |

| tears shed by a Muslim |

| tears of bitter pride |

| tears of deep sadness at the death of an uncle leaving a father the only witness to the family’s life in Poland |

| tears shed by an Israeli while listening to Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto |

| tears shed by a North American while discussing the settlement of property after 11 years of marriage |

| tears shed by a Buddhist |

| tears shed by a lesbian when Andy Sipowicz witnessed the murder of his wife Sylvia in a courtroom shooting on NYPD Blue |

| tears shed under pressure of a deadline |

| tears shed by a Palestinian in despair of the invisibility of justice for her people |

| tears shed in recognition of the deep, ongoing unhappiness of family relationships tears of frustration shed by a toddler |

| tears shed over the demise of a promise of love |

| tears shed by a Chinese woman under a full moon |

| tears shed after an orgasm |

Chutzpah

1998

installation view, 160 strand lights with eggshells, variable dimensions

chutzpah noun, colloquial impudence, bravado, gall [Yiddish]

for Felix

1998

installation view, 160 strand lights with eggshells, variable dimensions

Composed ofeggshells and a string of 160 small lights, this installation was created for the 1998 Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras exhibition Edifying Sappho and Socrates, which proposed monuments to gay and lesbian culture. for Felix is both a tribute to Felix Gonzalez Torres’ poetic generosity and an expression of vulnerability, fecundity and resilience. The title turns on the dual meaning of `felix’, Latin for happiness.

Begging bowls

1996 - 1998

average size 17cm x 8cm

molding wax with mixed media including teeth, hair, petals, pins, peppercorns, New York subway tokens, salt

Burned, teeth and hair

Passage, New York subway tokens, salt

All that glitters, o rings

Bowl pierced with Kabbalistic illustration of the heavens

Spice, peppercorns

Beauty, petals and pins, exterior

Beauty petals and pins, interior

your name

1996

flour, kosher salt, 5m x 5m

your name references a landscape of desert and ocean; passage across continents (my parents’ migration from Europe to Australia), the water’s edge (the beach, yearned for in New York where the work was created). Kosher salt is considered to be ‘purer’ than ordinary salt and is used in the process of purifying (koshering) meat, and also in ordinary cooking. I chose salt and flour for their colour, texture, domestic and symbolic properties. After all, cooking and eating play paramount roles in Jewish culture, expressions of love often channelled through food.

The ridges, resembling sand dunes or waves were created by pressing my fingertips into the flour, the symbols which appear to be at the mercy of the tide’s ebb and flow are taken from Eastern European tombstones. Some define the interred by their profession (the scissors representing a tailor), or inherited status (the hands in a pose of benediction indicate that the person descended from Aaron, the high priest).

The Hebrew word ‘shimecha’ –‘ש מ ך’ means ‘your name’, and can be understood on many levels. Your name goes forward into the world representing you and remains behind after you; when you imagine a loved one, you might say their name to draw their presence closer. your name also addresses the Jewish God, whose name it is forbidden to utter, in and for whose name, so many have died. your name is question, meditation and accusation, expressing my own uncertainty about God’s existence.

in my father’s house

1996

composed of five molding wax sheets annotated with pompoms and eggshells

dimensions variable

Ultima

1994

six 3m x 1.25m sheets of translucent imprinted with images, 30 kg of sieved paprika over a semi-circular area of 7 square metres

Ultima proposed a collective space of commemoration. The work mourned the indelible scar of the Holocaust on the Jewish psyche and spoke of loss, chance, survival and the ethical necessity to be a witness, even metaphorically, to history. Created upon my return from Hungary in 1993, Ultima was composed of six three metre by one and a quarter metre translucent tracing paper sheaths, each imprinted with an image gathered from my research in Hungary. It marked the 50th anniversary of the deportation of 300,000 Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz, a deportation which proceeded even though the Germans knew the war was lost.

I combined photographs I had taken from my parents’ birthplaces with three maps tracing the geographical, physical and ideological movements of the European Jewish community. Drawn up out of a semi-circular bed of paprika which resembled a bloody landscape denying entry, these six sheaths silently question: how does one measure pain? How does one measure displacement?

The Turkish Bath House Installation

1993

30 kg paprika, poppy seed and salt

The Turkish Bath House Installation was created while on a scholarship to the Fine Arts Academy of Budapest. I sifted a carpet of paprika, salt and poppyseed in the empty bath of a disused faux Turkish bath house in Budapest, sequestered by the small but vital art community as a contemporary art space. I fashioned three images gleaned from my research into my family’s history and that of the Jews of Hungary: the white pointed hat which medieval Jews were compelled to wear as identification (a precursor to the yellow star of WWII), a Turkish turban and an upturned bow and arrow insignia.

In the centre of the paprika ‘carpet’ lie the first and last letters of the Hebrew alphabet, my own notation symbolising the first and last and all that lies between. The bow-and-arrow image (at first glance also resembling a hat), was inscribed on the wall of a small 17th century synagogue in the old city of Buda. The text reads: The strong man of bow will be corrupted and the powerless will become powerful. The Lord shall bless you and hold you. A message of hope and comfort to the Jewish community, which endured frequent expulsions from medieval Hungary on pretexts of spreading plague or enacting ritualistic murder (blood libels).

In 1541, Buda, the capital of Hungary, fell to the Turks who occupied a third of the country for 150 years. Jews living under Turkish domination experienced a respite from anti-Semitic violence - they could practise their religion, trade freely and abandon discriminatory markings. The Turks, I discovered with some surprise, were also responsible for bringing paprika and poppy seeds to Hungary.

The Turkish Bathhouse Installation celebrated strength and endurance in the face of oppression and represented a triumphant return to the city from which my parents had been forced to flee.

The deep red paprika which I had thought to be quintessentially Hungarian, also evoked the landscape of Australia’s centre, in a neat exchange of material symbolism. A year later, this pivotal journey to Hungary also fuelled Ultima, where the bed of sifted paprika took on malevolent overtones, suggesting the blood soaked soil of Europe, from which my parents sought to escape.

Stereotype/other

1992 - 93

acrylic and mixed media, 28 canvases each 25cm x 30cm

Stereotype/other proposed an alternate journey into the experience of otherness, and examines anti-Semitism, propaganda and the complex relationship of `the other' to mainstream society.

Twenty-two anti-semitic images depict the incongruous and irreconcilable characteristics attributed to Jews from medieval Romania to 20th century Australia, exploring the construction of ‘the Jew’ as a twilight figure built from centuries of anti-Semitism. The stereotype of the demon enemy: greedy, lecherous, lusting after world domination and the blood of children.

These images, researched from diverse sources, are punctuated by six panels depicting the yellow star Jews were forced to wear as identification in different European countries during WWII. These panels are overlaid with fine white sand bespeaking burial and silence. The inverted triangle installation opposes notions of progress and optimism.

Crossing Territories

1991

22 panels each 16cm x 21cm, mixed media on canvas

Crossing Territories was the first work which actively wove the different strands of my Jewish, European and Australian identity together, essentially naming one culture in the language of another. I continue to draw on the visual experiences, physical sensations and knowledge I gained in my passage around and across Australia. This significant journey opened my understandings of space, indigenous culture, nature and the sublime.

Crossing Territories developed from an eight month journey around Australia in 1985/86. These twenty-two postcard-sized paintings represent missives sent along a journey across physical and cultural unknowns; a joyous gathering of experiences, knowledge and actual materials, exploring and interacting with the natural environment. The Hebrew alphabet acts as the structure for articulating relationships between my Jewish cultural inheritance and aspects of the physical and psychological landscape of Australia.

I gathered parrot and emu feathers, rocks seamed with opal, tyre treads, seeds and echidna quills with which to overlay Jewish and European culture on the Australian environment in a process of naming and claiming ownership of my place and identity.

The nuances of culture as expressed through language have always interested me. The Hebrew alphabet, composed of twenty-two letters has been a rich graphic and creative source. It is the only alphabet whose letters function as numbers, which, apart from their everyday usage, also contain mystical resonances as expounded in the Kabbalah.

Crucial to these small detailed paintings are the writings of Primo Levi particularly The Periodic Table. This magical narrative poem contains twenty-one autobiographical chapters, each named after a chemical element and reflecting its properties. Levi’s structuring device, with the unexpected and moving juxtaposition of the objective elements with the subjective narratives, continues to resonate with me.

1. Davis, Lévinas: An Introduction, 46.

2. Lévinas, Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority, 11/26.

3. Ashley Carruther, Rilka Oakley & My Le Thi, Isle of Refuge Catalogue, Ivan Dougherty Gallery, The College of Fine Arts, UNSW 2003.

4. On 26 August 2001, in response to a Mayday signal from a ship in international waters near Christmas Island, the Australian Government sent a plea to nearby vessels to conduct a search and rescue mission. The Tampa, a Norwegian cargo ship responded to the call, finding a 35metre Indonesian fishing boat in serious trouble after a storm, with 438 asylum seekers aboard who were planning to claim refugee status in Australia. The Howard Government refused to accept the refugees.

5. From A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments, 1977, Roland Barthes (1915 - 1980) .